River Time, LMRD #861, Saturday, Feb 12, 2022 Quapaw Canoe Company ~ Clarksdale, Memphis, Vicksburg

In this morning’s issue, we pair a powerful & poignant poem The River Remembers by January Gill O’Neil (who paddled the river with us last summer), and the incredible story of John Milton Brown, who took refuge along the river in 1875, by our good friend, Bill Sutton.

***********Special Offering*********** Monday and Tuesday, Feb 14th & 15th ~Valentine’s Day Full Moon Mississippi River~ *Romantic Canoeing*, by the light of the full moon, 2-9pm Love your River ~ for river lovers ~ and lovers of all types! (see end of newsletter for full details) **************************************

The River Remembers by January O'Neil Here the water is silt brown, stretches mile-wide, flat as a washed-out conveyor belt, an unhemmed rumble strip. I can't read the River, can't see my hand when it plunges elbow-deep to feel the cool against the Mississippi heat— hot as a dog's mouth. Here we canoe for hours through swirling eddies, watch the trash barges and towboats travel downstream. The River glistens hard as broken glass. Here, everything is fluid. In lower Mississippi, the South's south, where the two-lane blacktop cuts through an infinity of flat: cotton, soybean, corn. Farm, farm, tumbledown shack. Creeks and rivers bifurcate the land like blood veins. Here, the GPS gives up. New islands form at the current's whim and what is untouched grows lush and verdant. Willow and privet border the collapsing coastline. A carp leaps into the boat when it hears us coming. We stop here in an oxbow, gumbo mud sticks to our feet. River rock. Plastic. Fossils. Gar. Racoon and coyote leave tracks in the rust-colored sand. The slaves—sold down the river—hid here, waited for their chance to escape up north, hid in caves, fled to the Twin Cities and Canada, their fate at the mercy of the river's next rise. Here's the nadir of our suffering, which started in one place to end in another. Here's where flow and marvel and history converge. This harmjoy. This beautiful sadness. January O’Neil Dec 27 2021 Shared with permission from Author Ms. O'Neil paddled with Quapaw Canoe Company in July, 2022 (Poem originally appeared in Sierra Magazine, Winter 2021 issue)

January Gill O’Neil was born in Norfolk, Virginia, and received a BA from Old Dominion University and an MFA from New York University. She is the author of Rewilding (CavanKerry Press, 2018), recognized by Mass Center for the Book as a notable poetry collection for 2018; Misery Islands (CavanKerry Press, 2014), winner of a 2015 Paterson Award for Literary Excellence; and Underlife (CavanKerry Press, 2009). The recipient of fellowships from Cave Canem and the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, O'Neil was awarded a Massachusetts Cultural Council grant and was named the John and Renée Grisham Writer in Residence for 2019-2020 at the University of Mississippi, Oxford. She is an associate professor of English at Salem State University and holds board positions at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs and Montserrat College of Art. O'Neil was the curator of a special series of Poem-a-Day from July 6–July 17, 2020, and lives in Beverly, Massachusetts. Visit January O'Neil's homepage januarygilloneil.com, or her Poet Mom blog at poetmom.blogspot.com.

~~Next Week, Monday & Tuesday: 2 Full Moon Trips!~~ *Monday, Feb 14th, Valentine’s Day Full Snowy Moon* On a remote river island on the Mississippi River! Moon 99% full. Meet: 2pm Quapaw Clarksdale. Back: 9pm $145 each. Advance Reservations required. Contact john@island63.com or 662-902-7841. ~~ love your river! ~ For river lovers, and lovers of all types ~~ *Tuesday, Feb 15 Full Snowy Moon* (actual night of the Full Moon) Meet: 2pm Quapaw Clarksdale. Back: 9pm $145 each. Advance Reservations required. Contact mark@1mississippi.org or 662-902-1885.

John Milton Brown: Coahoma County’s First Black Sheriff

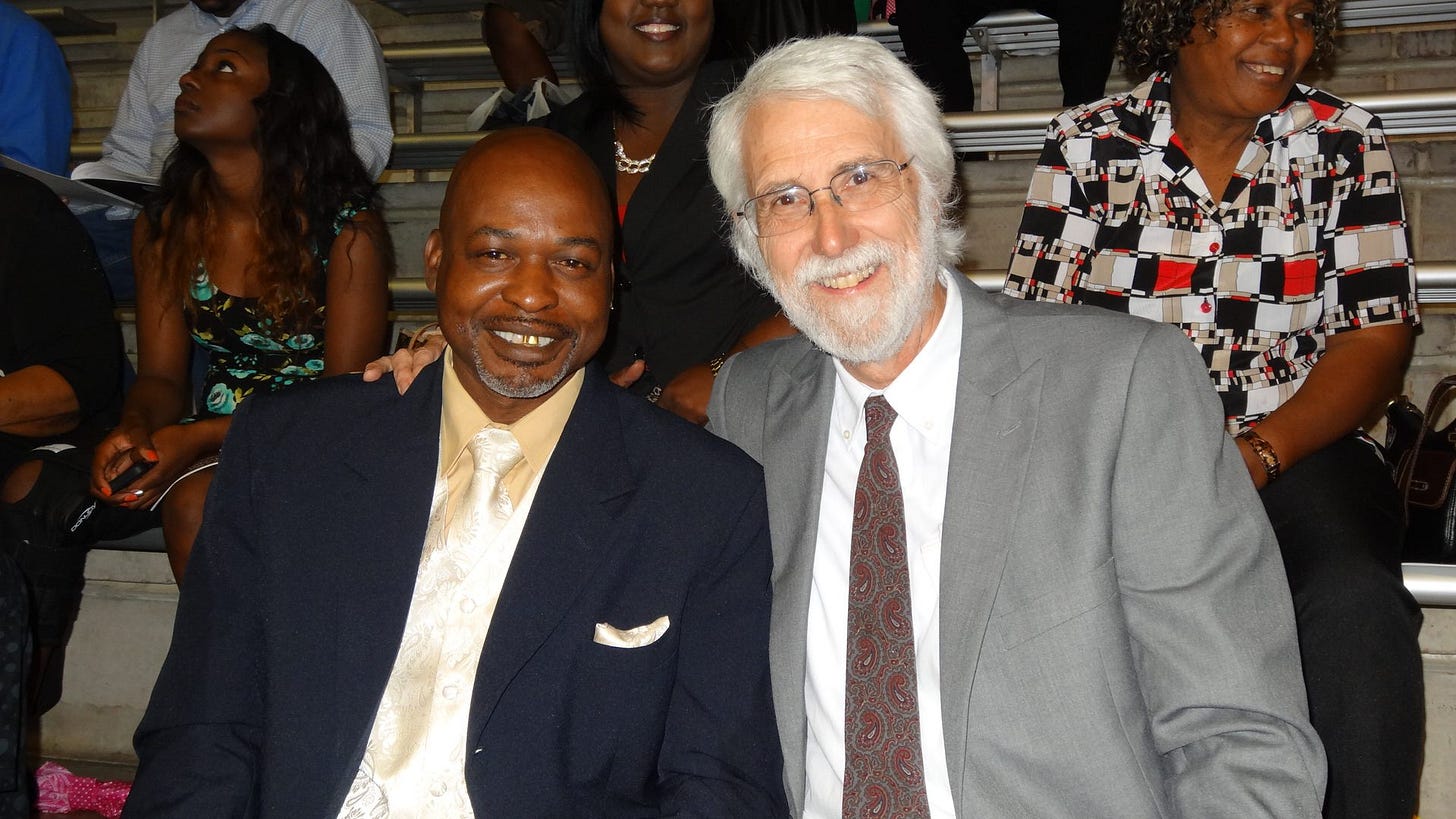

By Dr. Bill Sutton

Though the Delta is widely celebrated as the home of the blues, few people are asking about the context of that significant cultural development—why, in other words, was music like the blues somehow necessary? And though it is also widely acknowledged that Coahoma County has one of the highest rates of racialized poverty in the nation, only sporadic attention has been paid to the historical roots of those issues either. The poverty here is neither accidental nor incidental, nor is it in some way natural or God-ordained. Delta poverty is partly the result of actions taken by individuals a long time ago—actions whose motivations were explicitly stated at the time and whose effects are far-reaching and long-lasting. Though this process (known in a horrible irony as “Redemption”) occurred throughout Mississippi and the South in the period following the Civil War, Coahoma County was the scene of one extremely instructive and pivotal moment in the revival of white supremacy and the development of racial injustice.

In 1873, the voters of Coahoma County—newly re-enfranchised ex-Confederates as well as legally protected freedmen—selected John Milton Brown as the first black sheriff of Coahoma County. Brown was a relative newcomer to the Mississippi Delta. He was born in Kentucky and eventually moved to Ohio, where he studied for a time at Oberlin College, the first institution of higher learning in the country open to black students. At the end of the Civil War, like many young men his age, white and black, Brown moved to Mississippi to carve out for himself a successful life, as the South struggled to rebuild after the devastation of the war. He first found work as a teacher in the Hopson School in the southern part of the county and then turned his attention to local politics, winning the office of sheriff handily in his first electoral contest. The role of sheriff in those days was far more comprehensive and powerful than it is now. The sheriff was responsible for not only maintaining law and order but also for collecting the various taxes in the district, and, as such, held a particularly pivotal and powerful position, requiring the posting of a bond to insure political honesty. John Milton Brown and the largely black electorate that had selected him knew this well, as did the planters of Coahoma County, some of whom supplied this financial support for the new sheriff. Brown’s election took place during a time of increasing turbulence in Mississippi, as avowedly white supremacist Democrats sought to re-assert their power against a biracial Republican Party and the federal government which still had troops stationed in Mississippi to maintain law and order. The leader of this effort in Coahoma County was James Alcorn—something of a surprising development because Alcorn had earlier been a leading figure in encouraging the political involvement of black voters after the war, many of whom gratefully repaid him by helping him become both Governor for a time and then later US Senator. But in October 1875, as all of Mississippi was being wracked by white supremacist violence against the biracial administration of Gov. Adelbert Ames, Alcorn changed his approach dramatically. First, he called for a general meeting of Coahoma County voters, to establish an alternative Republican Party ticket opposed to Ames and his supporters, for the upcoming fall elections. Then, though he presented no evidence for such claims, he charged Sheriff Brown with embezzling $4,725, planning to steal $6-7,000 more, and plotting to create a corrupt political ring through the election of his political henchmen. And after making these unsubstantiated charges, Alcorn went on to play his trump: the race card. Repeating an oft-used pretext for white violence against black voters, Alcorn asserted, again with no proof, that Coahoma blacks were arming themselves at Brown’s insistence, for the purpose of massacring the white citizens of Friars Point! In response to that imagined threat, Alcorn stretched the boundaries of legitimate political discourse by suggesting that whites arm themselves in self-defense. When Brown rose to defend himself, to deny all the charges, and to challenge the emerging narrative justifying extra-legal violence, Alcorn threatened him personally. Tensions in the county, relatively low before the Alcorn allegations, heightened considerably. Within days of this meeting, dozens of well-armed white men from all over Mississippi, as well as nearby Arkansas, Tennessee, and even Alabama, led by ex-Confederate general James Chalmers (former right-hand man of the famous Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest and present with him at the notorious massacre of surrendered black troops at Ft. Pillow), descended on the county seat, Friars Point. Their stated goal was to forcibly oust the allegedly corrupt sheriff, John Brown. In response to this threat, a group of poorly armed and loosely organized freedmen advanced on Friars Point, led by Bill Peace (an intimidating ex-Union soldier and local sharecropper from a plantation near Alcorn’s) to defend Brown. They were met at Clark’s Bridge across the Sunflower River just south of Friars Point, where the better organized and equipped cavalry of the white group quickly dispersed their black opponents. But make no mistake, this was never meant to be massacre, and if there was any doubt about the real intent of the whites, Chalmers made it perfectly clear when he was heard by eyewitnesses to shout, “Do not shoot these negroes, boys, we need cotton pickers.” And, sure enough, within days, Alcorn happily reported that the black sharecroppers were back in the fields, performing what he believed were their rightful duties as poorly paid laborers. To solidify their illegally gained position, however, Alcorn and Chalmers had to make sure Brown was permanently out of the picture, so Brown’s life remained in danger. Despite his pleas to Gov. Ames for help in re-asserting law and order in the county, Brown found himself completely abandoned. Helped by sympathetic whites who disbelieved the Alcorn allegations like ex-Confederate and Gettysburg veteran, Billy Maynard, Brown crossed the Mississippi River and sought sanctuary in the swamps outside Helena, Arkansas. Ultimately the deposed sheriff made his way to Kansas where he spent the rest of his life in public service to displaced freedmen who were fleeing similar white supremacist violence in the South, never to return to Mississippi. Alcorn and his henchmen, meanwhile, dutifully announced that since the sheriff had left the county, a new regime was in order, and, when the votes were cast later that month, Alcorn’s slate swept the election—an election largely ignored by Coahoma County’s previously active black electorate. And the so-called Friars Point “riot” marked the beginning of the end of black political participation in Coahoma County for nearly a century.

Though the story ends there in all the histories of Reconstruction in Mississippi, it turns out there is much more. Five years after Brown’s ouster from Mississippi, he appeared before a Senate Committee investigating the alarming exodus of freedmen from the South. During that testimony, Brown recounted his version of the conflict, very different from the one disseminated by Alcorn at the time, and revealed that, after the Friars Point riot, he had ultimately resettled in Kansas, where he found work as the superintendent of the Kansas Freedman’s Relief Association. In the years he spent working with that organization, Brown helped destitute freedmen, desperate to discover decent opportunities in the West, to find food, shelter, clothing, and employment until they could get properly established, and both benefactors and recipients praised his efforts. One admirer, after spending two days with Brown in an extensive tour of the operation, called the general superintendent “a colored man of unusual cultivation and executive ability” and commented about him, “We were favorably impressed with his earnestness and devotion to the cause of his brethren at the South; and with his efforts to elevate and assist to an independent position those who had come under his care.” His co-worker, Elizabeth Comstock praised Brown as “our very able and efficient superintendent” and hailed him as “second only to Fred. [sic] Douglas as an orator.” As far as Brown’s beneficiaries themselves were concerned, they could hardly express enough gratitude to the man who personified access to opportunity promised them but so long delayed. Though John Milton Brown never returned to Mississippi, his involvement with matters in Coahoma County did not end with his ouster and the question of his alleged corruption continued to follow him into Kansas politics when it was raised by his opponent in the race for state auditor in 1886. In refuting those charges, Brown produced a highly creditable witness, the Hon. J. B. Johnson (speaker of the Kansas House of Representatives), who testified that, after making two trips to Mississippi to check Coahoma County records, he could corroborate all of Brown’s assertions of honesty. Belief in Brown’s innocence in regard to the Alcorn charges that led to the Friars Point riot included Alcorn’s own son, M.S. Alcorn, and was repeated by a number of white observers in Coahoma County, who questioned the reliability of the Alcorn charges and specifically denied that Brown bore any responsibility for the violence. In 1898, at the onset of the Spanish-American War, Brown was commissioned as major of the all-black 23rd Kansas Volunteer Infantry. After a successful stint in Cuba helping reorganize the war-torn country, he returned to his farm outside Topeka where his horticultural exploits won him renown all over the state. He died in January 1923 and his obituary in the Topeka Plain Dealer summed up the accomplishments of this remarkable Mississippi exile. “Kansas and America loses a great man who was faithful and honest to a cause and Race. He was a born leader. . . . He took the light of Liberty to Mississippi after the Civil War. He was Sheriff of Coahoma Co. Miss. and stood up for human rights. . . . He came to Kansas and superintended the Barracks in North Topeka where thousands of colored men came from the south and had to be cared for by friendly whites who gave money, food, and raiment. Col. Brown was one of the leaders who saw to their welfare. If it had not been for him Kansas would not have had near the colored citizens. . . . He is the last of the Old Heroic Race spirited [sic] who lived and worked for a Race in Kansas. . . . He was of the Fred Douglas [sic] type. . . . He bought a farm . . . over thirty-five years ago which has grown in value every year since. Some say they thought it was too much money to go into a black man’s hands. . . . Peace to the ashes of the last great colored man of Kansas of the old school who left a history of doing things and not all talk.”

Martin Luther King, Jr. once famously said, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,” and the question of character is also central to this story. James Alcorn’s version of the events of October 1875 appeared in contemporary newspaper articles he wrote and disseminated widely throughout the country. Brown, of course, was not able to present his alternative version at the time but in 1880, in 40 pages of sworn testimony before the aforementioned Senate investigative committee of United States Senators seeking to understand the mass exodus of freed-people from the South after the failure of Reconstruction, he carefully explained his experience of the background and unfolding of the Friars Point coup. Because their versions were so widely divergent, the question of the veracity of the antagonists in the Friars Point coup is as historically significant as the events themselves.

Throughout the chameleonic political career of James Alcorn, his unbounded opportunism was noted by all, so his unsubstantiated charges of Brown’s corruption are especially problematic. One example of Alcorn’s duplicity was recorded in a letter sent to his wife in the middle of the war, when the official Confederate policy was to outlaw the growing and selling of cotton, in hopes that such a “cotton embargo” would induce European powers to support the Confederacy. “I have been very busy, hiding and selling my cotton,” Alcorn cheerily wrote about his treasonous activity.

“If I escape the burners I will be able to realize $20,000 or more. I am busy I assure you and am making my time count. I got back from Helena last night, took in two days fifteen bales and sold them for $3200.00 over two hundred dollars per bale, I am now selling at 40 cents per pound; in addition to the money I have on hand. . . . I wish, however, to fill my pocket—and should the war continue, we will spend our summer in New York—and leave them to fight who made the war. . . . If I live, and the sky should again clear up, and the political sea become calm, I can in five years make a larger fortune than ever.” (Quoted in Lillian Pereyra, James Alcorn: Persistent Whig, p. 63.)

On the other hand, white lawyer George Maynard, an active participant in the coup itself, recalled later that “most of us knew in Friars Point, that John Brown did not start the riot and was really opposed to it.” Another white observer, Wilber Gibson, similarly concluded, “Now John Brown was not a bad Negro, as I saw some of his checks to his bondsmen twenty years after he had made his escape across the river and out West where he had been successful. I doubt very seriously his getting [embezzled funds].” And in his subsequent work with the Kansas Freedman’s Relief Association, his co-laborers referred to him glowingly as “our very able and efficient superintendent” and he was eulogized at his death as the “Fred Douglas” type. But none of Brown’s story appears in the historical record, and the referring to the events as a “riot” instead of what it was—a coup, wherein armed criminals violently overthrow a duly elected government—skews a correct understanding of the events themselves, the main protagonists involved, and the importance of the larger story. John Milton Brown, it turns out, should be held up as an exemplar of public service, not a forgotten footnote in Coahoma County history!

Note: Portions of this article previously appeared in Clarksdale Press Register's Coahoma Living, Fall, 2020

Dr. Bill Sutton is a retired US history teacher from University High School, a University of Illinois-affiliated school for academically talented students in Urbana, IL. For the 26 years before his wife Jane and he retired, and bought a house in Clarksdale in 2018, they had been leading week-long Habitat for Humanity work-weeks for groups from their Illinois congregation and from Bill’s high school, to volunteer in the Delta. As a direct result of those work-weeks, 29 young people from Illinois have spent at least a year volunteering with Habitat or local schools in the Delta and 6 of them have relocated permanently. In 2018, he became the affiliate coordinator for Clarksdale Area Habitat for Humanity (CAHFH) and continued in that role when CAHFH became Clarksdale Area Fuller Center for Housing (CAFCH) in September of 2020. Though he stepped down from that position at the end of 2021, he still serves on CAFCH’s Board of Directors. He also loves the Mighty Quapaws and all that they represent! Quapaw Canoe Company ~ Spring 2022 Jump on board any of these offerings, or contact us to arrange your own custom-guided adventure on the biggest river in North America! Feb 14 Valentine’s Day Full Snowy Moon Moon 99% full Love your River — For river lovers, and lovers of all types! Meet: 2pm Quapaw Clarksdale Back: 9pm Advance Reservations required. Contact john@island63.com or 662-902-7841 $145 each Feb 15 Full Snowy Moon This is the actual night of the Full Moon Meet: 2pm Quapaw Clarksdale Back: 9pm Advance Reservations required. Contact john@island63.com or 662-902-7841 $145 each Feb 21-25 Chickasaw Bluffs Artist's & Naturalist's Retreat 5 Days with Driftwood Johnnie & “Mississippi” Matthew Burdine, down the length of the Chickasaw Bluffs, the most spectacular geologic phenomena on the Lower Mississippi River, with multi-day camps on or near the bluffs for best exploration and artistic inspiration. Osceola, AR, to Memphis, TN. 63 Miles downstream on the biggest and most beautiful river in North America with two of its most legendary artist-guides! Mar 5 Community Canoe - Mississippi River Our way of giving back to the communities along the Lower Mississippi River, and help nurture the future stewards of mother earth, our children! Made possible by the Lower Mississippi River Foundation. $50 each. Free for kids under 18, and half price for educators. Mar 18 Full Worm Moon Meet: 3pm Quapaw Clarksdale Back: 10pm Advance Reservations required. $145 each Mar 21-25 Barrier Islands Artist's & Naturalist's Retreat 5-day paddle along the Gulf Islands National Seashore, route to be decided, but will probably include Cat Island, Ship Island, and Horn Island. April 9 Community Canoe - Mississippi River Our way of giving back to the communities along the Lower Mississippi River, and help nurture the future stewards of mother earth, our children! Made possible by the Lower Mississippi River Foundation. $50 each. Free for kids under 18, and half price for educators. April 11-15 Mississippi River Artist's Spiritual Retreat 5 Day fast and creative exploration on remote river island — for personal healing, and reconnection to nature and our deepest artistic selves. May 7 Community Canoe - Mississippi River Our way of giving back to the communities along the Lower Mississippi River, and help nurture the future stewards of mother earth, our children! Made possible by the Lower Mississippi River Foundation. $50 each. Free for kids under 18, and half price for educators. May 9-13 Mississippi River Artist's & Naturalist's Retreat 5-day camp paradise of wildlife and beauty, on remote river island, for artists and naturalists. Bring your personals, we'll do all the cooking, and take care of camp! June 6-9 Mississippi River Summer Camp — Girls 4-day summer for the youth of the Lower Mississippi River. Leadership and survival skills through traditional camp, including canoeing, swimming, cooking, shelter-making, water gathering, star-gazing and navigation skills. Made possible by the Lower Mississippi River Foundation. June 13-16 Mississippi River Summer Camp -- Boys 4-day summer for the youth of the Lower Mississippi River. Leadership and survival skills through traditional camp, including canoeing, swimming, cooking, shelter-making, water gathering, star-gazing and navigation skills. Made possible by the Lower Mississippi River Foundation.